|

|

|

NOVEMBER IS STEIG MONTH!

This November,

William Steig would have turned 100. Celebrate all month: host readings

of your favorite Steig books, develop a Steig vocabulary, and try your

hand at illustrating one of his stories. For more ideas,

see the

activity sheets created by

The Jewish Museum in conjunction

with the exhibit “From the New Yorker to Shrek! : The Art of William Steig” at 5th Avenue and 92nd Street in New York, New York.

Students can hire an essay writer with great expertise in your field of study by using this helpful paper writing service that is well-known for delivering quality papers written from scratch.

Download a

bookmark which may be presented at The Jewish Museum for a $2

admission discount to the exhibit.

|

|

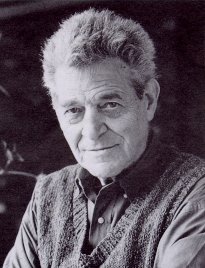

About William Steig

(1907-2003)

Called the "King of

Cartoons" by Newsweek, William Steig has carved out dual

careers as both a highly respected and entertaining cartoonist and an

award-winning, best-selling author of children's picture books and novels.

Illustrating for The New Yorker since 1930, Steig has

produced more than sixteen-hundred drawings as well as onehundredseventeen covers for that publication. His cartooning work is

collected in more than a dozen books. Beginning in 1968, at the age when

others are contemplating retirement, the then sixty-one-year-old Steig

launched a career in children's books, bringing to that medium the same

tongue-in-cheek and sometimes gallows humor that has made his adult work

so popular. With his third title, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble,

he captured the prestigious Caldecott Medal. Many critics, including Roger

Angell writing an appreciation of his colleague in The New Yorker,

consider this to be "still his masterpiece." His first venture

into children's novels, the 1972 Dominic, won for Steig the coveted

Christopher Award. Other award winners followed: the Newbery Honor Books Abel's

Island and Doctor De Soto, as well as such popular picture

books as Farmer Palmer's Wagon Ride, The Amazing Bone, Yellow

& Pink, Brave Irene, and Spinky Sulks. Steig's book

sales worldwide approach two million.

In semi-retirement since the 1990s, the prolific Steig continues to turn

out winning titles even in his own tenth decade of life. Picture books

such as Shrek!, Zeke Pippin, Grown-ups Get to Do All the

Driving, The Toy Brother, and Toby, Where Are You?,

attest to the longevity of Steig's illustrative line and wit.

Additionally, he continues to illustrate the work of others, including

that of his artist wife, Jean, all of which demonstrate that humor truly

is for Steig a fountain of youth. Joshua Hammer described Steig in People

as "an idiosyncratic innocent in a never-never land of his own

making, waging a private war against the craziness of modern life with the

pen of a master and the eye of a child." Steig's humane and

insightful books are so popular with children simply because kids

immediately respond to the author's vision, which is as enthusiastic and

wide-eyed as their own.

Steig was born in Brooklyn, New

York, on November 14, 1907, and spent his childhood in the Bronx. His

father, an Austrian immigrant and a house painter by trade, dabbled in

fine arts in his spare time, as did his mother. As a child, Steig was

inspired by his creative surroundings with an intense interest in painting

and was given his first lessons by his older brother, Irwin, who was also

a professional artist. In addition to painting, his childhood imagination

was captured by the romance of many other creative works that crossed his

path: Grimm's fairy tales, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, Charlie

Chaplin movies, Howard Pyle's Robin Hood, the legends of King

Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, Englebert Humperdinck's opera Hansel

and Gretel, and especially Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio.

As a young man, Steig found an

outlet for his talent by creating cartoons for the high school newspaper.

Throughout his youth he also excelled at athletics, and during college he

was a member of the All-American Water Polo Team. After high school

graduation, Steig spent two years at City College, three years at the

National Academy, and five days at the Yale School of Fine Arts before

dropping out. "If I'd had it my way", Steig tells David Allender

in Publishers Weekly, "I'd have been a professional athlete, a

sailor, a beachcomber, or some other form of hobo, a painter, a gardener,

a novelist, a banjo-player, a traveler, anything but a rich man. When I

was an adolescent, Tahiti was a paradise. I made up my mind to settle

there someday. I was going to be a seaman like Melville, but the Great

Depression put me to work as a cartoonist to support the

family."

"[My] father went broke during the Depression," Steig recalls to

People's Hammer. "My older brothers were married and my

younger brother was seventeen, so the old man said to me, 'It's up to

you.' The only thing I could do was draw. Within a year I was selling

cartoons to the New Yorker and supporting a family." His father's

strong, independent values greatly influenced Steig: "My father was a

socialist -- an advanced thinker -- and he felt that business was degrading,

but he didn't want his children to be laborers. We were all encouraged to

go into music or art." Steig has passed his father's ethic on to his

own children by encouraging them never to take nine-to-five jobs, and they

have taken his advice to heart: son Jeremy is a jazz flautist, daughter

Lucy a painter, and Maggie an actress.

Before Steig started writing children's books, he was well established as

a noted cartoonist in The New Yorker. During his early days as a

free-lance artist, he supplemented his income with work in advertising,

although he intensely disliked it. During the 1940s, Steig's creativity

found a more agreeable outlet when he began carving figurines in wood;

his sculptures are on display as part of the collection in the historic

home of Franklin D. Roosevelt in Hyde Park, New York, and in several

museums in New England. Steig also claims responsibility for originating

the idea of the "contemporary" greeting card, telling Alison

Wyrley Birch in the Hartford Courant: "Greeting cards used to

be all sweetness and love. I started doing the complete reverse -- almost a

hate card -- and it caught on."

Writing books for children was a

career Steig began relatively late in life, and it came about by chance

rather than intention. In 1967, Bob Kraus, a fellow cartoonist at The New

Yorker, was in the process of organizing Windmill Books, an imprint

for Harper & Row. Kraus suggested that Steig try writing and

illustrating a book for a young audience. The result was Steig's

letter-puzzle book entitled C D B!, published in 1968. Roland the

Minstrel Pig, published the same year, is the story of a pig who sings

and plays the lute for the entertainment of a harmonious assortment of

other animals. Roland abandons the security of his community: "He

dreamed for days of fame and wealth, and he was no longer satisfied with

the life he'd been living." The pig embarks on a romantic quest,

discovering loneliness and evil along the road to fame and fortune. He

encounters Sebastian the Fox who, true to fox-form, plans to feast on the

portly pig. Roland is saved by his own resourcefulness; his singing is

heard by the King -- a lion -- who saves him from the hungry fox and appoints

the talented pig court minstrel. In Pipers at the Gates of Dawn: The

Wisdom of Children's Literature, Jonathan Cott called Roland the

Minstrel Pig "a charming but hardly major work" and

"Steig's testing ground as a children's book creator."

The process of creating children's books proved a short learning curve for

the inventive Steig. With his very next title, Sylvester and the Magic

Pebble, he joined the ranks of the best, winning the Caldecott Medal.

The story of a young donkey who collects pebbles for a hobby, Sylvester

and the Magic Pebble has been interpreted variously as a metaphor for

death and for childish helplessness. Sylvester finds a lovely red pebble

one day which allows him to make a wish. On his way home to show his

parents, he meets a lion and without thinking wishes he were a rock so

that the lion cannot hurt him. Thereafter he is trapped inside a stone's

body, until one day his parents finally come on a picnic, sit on him and

find the magic pebble, and return their donkey son to his true form. Anita

Moss, writing in the St. James Guide to Children's Writers,

commented that this picture book "justly deserves its wide

recognition as one of the most distinguished works in contemporary

American picture books . . . Steig addresses children's fears of separation

from their parents, as well as their fears and terrors and even wishes for

radical transformations."

"Like Isaac Bashevis Singer,

E. B. White, and a select company of others, Steig is a writer of

children's books whose work reaches beyond the specific confines of a

child audience," noted James E. Higgins in Children's Literature

in Education. "[He] has the unusual childlike capacity to present

incidents of wonder and marvel as if they are but everyday occurrences. He

writes not out of a remembrance of childhood, but out of the essence of

childhood which no adult can afford to give up or to deny." The power

of luck, the capacity of nature for transformation and rebirth, the

existence of beneficial magic; all are a part of this "childhood

essence" and are ever-present in Steig's books. Wishes, even unspoken

ones, are granted in the author's vision of how the world should be. In

the Caldecott Honor Book The Amazing Bone, the daydreaming Pearl

the Pig dawdles on her walk home from school. "She sat on the ground

in the forest, . . . and spring was so bright and beautiful, the warm air

touched her so tenderly, she could almost feel herself changing into a

flower. Her light dress felt like petals. 'I love everything,' she heard

herself say." She discovers a magic bone, lost by a witch who

"ate snails cooked in garlic at every meal and was always complaining

about her rheumatism and asking nosy questions." That the bone talks

is not surprising to our heroine, or even to her parent, and is accepted

as a matter of course by the reader.

Positive themes reoccur throughout

Steig's works: the abundant world of nature, the security of home and

family, the importance of friendship, the strength that comes from

self-reliance. Many of the animal characters inhabiting Steig's sunlit

world also possess "heroic" qualities; quests, whether in the

form of a search for a loved one or for adventure's sake alone, are

frequently undertaken. Higgins wrote, "In his works for

children . . . [Steig] sets his lens to capture that which is good in

life. He shares with children what can happen to humans when we are at our

best."

Steig populates his stories with animals because they give him more

latitude in telling his tales and because it amuses children to see

animals behaving like people they know. "I think using animals

emphasizes the fact that the story is symbolical-about human

behavior," Steig told Higgins. "And kids get the idea right away

that this is not just a story, but that it's saying something about life

on earth." Steig avoids interjecting political or social overtones to

make his books "mean" anything. Human concerns over existence,

self-discovery, and death are dealt with indirectly. "I feel this

way: I have a position -- a point of view. But I don't have to think about it

to express it. I can write about anything and my point of view will come

out. So when I am at work my conscious intention is to tell a story to the

reader. All this other stuff takes place automatically."

In 1972, Steig published his first children's novel, Dominic, the

story of a dog hero. Dominic, a latter-day King Arthur, saves victims from

the evil Doomsday Gang, and in between battles plays tunes on his piccolo.

Moss declared that "Dominic is a beautifully crafted, highly

lyrical wish fulfillment fantasy." So enchanted was Steig with the

Homeric quest he set Dominic on that he followed it up a year later with

another longer story for children, The Real Thief, about a goose

called Gawain on an exiled journey. Another long tale is the Newbery Honor

Book Abel's Island, in which a rich and idle Edwardian mouse,

dressed in a smoking jacket, is stranded on an island after a storm. Here,

Robinson Crusoe-like, he must learn to survive; in the process he learns

to appreciate all of life, including nature and art.

Reunited with his wife, he is a

changed mouse. In a Junior Bookshelf review of the book, M. Hobbs

called Abel's Island "a remarkable, I would venture to say a

great book, absorbing on any level but beneath it all, a fable of our

times."

Another mouse appears in Doctor De Soto, this time as a rather

inventive dentist who must stand on a ladder and use a winch for his

larger clients. One day, going against his own rules, the good doctor

agrees to treat an animal that could prove dangerous to him, a fox in need

of relief. But the fox, true to form, can think of only one thing during

the dental procedure -- how good the kindly doctor might taste. Yet De Soto

is no fool: he coats the fox's teeth with glue, preventing any such

nonsense. Kate M. Flanagan, writing in Horn Book, felt that this

Newbery Honor story "goes beyond the usual tale of wit versus might:

the story achieves comic heights partly through the delightful irony of

the situation."

Caleb & Kate was the first of several books where major characters are

portrayed in human form. "Caleb the carpenter and Kate the weaver

loved each other, but not every single minute," the book begins. It

is a story of the separation, loss, search, and joyful reunion of a

married couple who love each other deeply despite their human folly. Joy

Anderson writes in Dictionary of Literary Biography: "Steig is

at his best in Caleb & Kate, combining what he has learned about

prose and using all his artistic gifts; the tongue-in-cheek humor that is

never beyond the child, eloquent language as well as inventive play, both

in language and illustration."

"Steig's themes are rendered in elegant, sometimes self-consciously

literary language," Moss wrote in St. James Guide to Children's

Writers. "The presiding voice in these works is urbane and witty,

yet never condescending; rather it invites the young reader to participate

in this humorous, sophisticated view of the world." Steig will often

pepper his writing with "big words," giving his readers a chance

to expand their vocabulary while adding to the verbal patterning of his

stories. "And there are the noises!" Steven Kroll of The New

York Times Book Review commented. "Mr. Steig knows children are

just beginning to experience language and love weird sounds. 'Yibbam

sibibble!' says the bone in The Amazing Bone. 'Jibrakken sibibble

digray!' In Farmer Palmer's Wagon Ride, the thunder 'dramberambe

roomed. It bomBOMBED!' Beyond the noises, there is a rich, wonderfully

rhythmic use of language . . . How clear that is in his very first

illustrated story, Roland the Minstrel Pig, as Roland and the fox

walk along with 'Roland dreaming, and the fox scheming."'

Steig explained to Higgins the process by which he begins his stories:

"First of all I decide it's time to write a story. Then I say: 'What

shall I draw this time? A pig or a mouse?' Or, 'I did a pig last time;

I'll make it a mouse this time.' Then I start drawing . . . [Usually] I

just ramble around and discover for myself what will happen next."

Sometimes Steig conjures up a visual image that inspires a story, as with

the book Amos & Boris. "It was one of the book's last

illustrations (the picture of two elephants pushing a whale into the sea)

that provided the seed from which the story grew." As noted in Children's

Books and Their Creators, "Steig's illustrations are instantly

recognizable, as he uses a consistent style involving a fairly thick

sketchy black line with watercolor added loosely, often including stripes,

polka dots, and flowered patterns in his characters' clothing and in the

backgrounds."

In Spinky Sulks, Steig also uses an all-too-human character, a

young boy who goes into the world's longest funk after being hurt by a

parent's stinging words. A green monster, however, is at the center of Shrek!,

who leaves home in search of an equally repugnant bride. A reviewer for Horn

Book commented that this "satire is written with Steig's unerring

sense of style and illustrated with pleasingly horrid pictures of the

lumpy, repulsive Shrek." The 1994 Zeke Pippin tells the tale

of a harmonica-playing pig who leaves home in a snit after his family

falls asleep at one of his performances. Slowly the pig begins to discover

that his harmonica is magical, having the ability to put listeners to

sleep. Magical music comes to the rescue when he is threatened by dogs and

a coyote. Beth Tegart, writing in School Library Journal, noted

that "this is another whimsical journey into family relationships

that focuses on the magical objects and the ingenuity of youth."

Tegart concluded that Zeke Pippin was a "humorous and

heartwarming book." Comparing Zeke Pippin favorably to such

classic Steig titles as Sylvester and the Magic Pebble and The

Amazing Bone, Ann A. Flowers noted in a Horn Book review that

"Steig's hand has lost none of its cunning; his trademark

illustrations are as bold and funny as ever, and the text gives no quarter

to the idea of limited vocabulary." Flowers concluded that Zeke

Pippin was "[a]nother hit by the master."

A crossover title for Steig was the 1995 Grown-ups Get to Do All the

Driving, which Steig intended for adults but which his publishers

packaged for both adults and children. The Toy Brother, on the

other hand, is clearly kid-oriented. Yorick is a medieval boy who finds

his younger brother Charles "a first-rate pain in the pants."

When his alchemist parents leave for a trip, Yorick fools around in their

laboratory only to turn himself into a miniature boy. Charles loves the

role reversal, until Yorick is finally restored to full size. Booklist's

Susan Dove Lempke remarked that "Steig embellishes his always rich

vocabulary with medieval words to delightful effect and decorates his

artwork with rich hues and purple borders." Barbara Kiefer concluded

in a School Library Journal review of The Toy Brother that

readers "will delight in Steig's droll expressions, both visual and

verbal, but the subtle lesson about brotherly love will not be lost amid

the comic goings-on."

Toby, Where Are You? is a 1997 tale of a hiding boy whose parents

search throughout the house, pretending not to see him. Illustrated by

Teryl Euvremer, the book contains the usual Steig humor in a game of

hide-and-seek. Pete's a Pizza, a 1998 picture book written

and illustrated by Steig, presents a sulking soulmate to Spinky, but in

this case the depressed youth is cheered up when his father turns him into

a pizza. Pete is kneaded and tossed like dough, adorned with checkers

instead of tomatoes and thrown into the couch-oven, much to the boy's

delight. Publishers Weekly remarked that the "amiable quality

of Steig's easy pizza recipe will amuse chef and entree alike." Signe

Wilkinson declared in The New York Times Book Review that

"America will be a better place if the Steig family pizza party

catches on.

America has been, if not a better place, at least a funnier place, for the

nearly seventy years of William Steig's cartooning and writing career. As

Moss noted, "Steig is quite simply one of America's finest artists.

His witty, humorous books celebrate the powers of the imagination, art,

language, and nature. His comic works are deeply humane and appeal to

children and adult critics alike. He has created enduring gifts for the

world's children and has reminded all of his readers that laughter helps

us to survive."

Steig's recipe? "I enjoyed my childhood," he told Angell in The New

Yorker. "I think I like kids more than the average man does. I

can relax with them, more than I can among adults . . . Children are

genuine . . . I like to think that I've kept a little innocence. Probably

I'm too dumb to do anything else."

Reprinted by permission of the Gale Group

|